This is the fourth in a series of articles about the kind of architecture that strikes a chord with me and why, brought to you because the world is full of incredible structures and too many of them pass us by.

Running a CGI company is an all-consuming, absorbing job…no two days are ever the same and because I have a passion for architecture and design, I always find my work intrinsically interesting. In fact, the more I work with different architects and bring their visions to life, the more I realise I should have trained to be one myself.

Yes, I was good at Art. And Science! If only there had been a switched on careers advisor pointing me in the right direction… But luckily life has a knack of gently pushing you towards your designated areas, even if you didn’t realise what they were in your mis-guided and mis-spent youth.

Ecological design is all around us…

From the small succulent placed by the bathroom window to expansive rooftop gardens on an apartment block – people are embracing nature in their living spaces and building designs. Nature is, indeed, a vital respite from densely-populated, concrete-heavy urban sprawl so it’s a welcome trend. By incorporating greenery into the designs of new apartment blocks and city centres, architects are simultaneously answering the global call to reduce our carbon footprint whilst addressing our underlying collective discomfort regarding climate change. The general aim of incorporating more greenery into city design appeals to the eco-conscious – the more plants, planters, trees, gardens, natural light and wildlife, the better. Or so you’d think – but there’s more to assimilating nature with urbanism than meets the eye, and if it’s not done in a careful, considered way, the benefits aren’t maximised.

Here are three areas where architects are trying their best to adapt their designs to work in synch with nature (with varied levels of success):

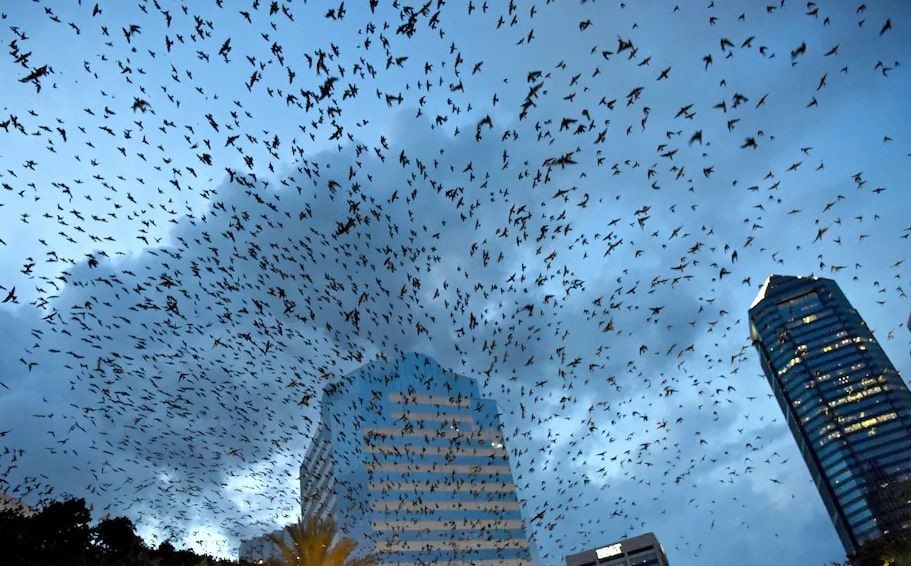

- Birds

We love natural light, and often covet south facing homes which let in the maximum amount of sunlight for the longest possible time (especially here in the UK). Poor weather and vitamin D deficiency guarantee that architects are going to prioritise house designs that maximise our wellbeing by increasing the spread of daylight across our homes.

However, this extensive use of glass is causing an estimated 100 million bird deaths per year in the UK (read more here). Unlike us, birds cannot understand glass and often think the reflected landscape is an actual landscape. You could be excused for thinking that monolithic glass-clad skyscrapers are the worst culprits, but in fact many birds collide with buildings at the tree line rather than above it. Which means that homes with large glass conservatories or smaller apartment blocks can be just as harmful as the larger buildings.

Sadly, there’s little that can be done with the structures already in place, but moving forwards where it’s not possible or conducive to design a building where glass sits only above the treeline and beyond, architects are beginning to introduce fritted glass, which is more easily seen by birds. This is glass which is printed with ink which contains ultra-small particles of ground-up glass. (You can read more about the ways architects are trying to address bird deaths here)

Because for all the benefits of glass, such as natural light and views, there are downsides, namely too much heat and lack of privacy. The use of fritted glass helps reduce glare, cuts cooling costs, and lowers the danger to birds. Additionally, it can also give the exterior a distinctive look with patterns ranging from simple shapes and gradients to intricate designs as can be seen in this example below, from architectural firm WHY, who recently completed a 60,000-square-foot annex to the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Kentucky. The exterior blends corrugated-metal panels and fritted glass, with stunning results.

2. Bees

More and more bees are being cultivated in our cities, which has got to be good news, right? You might think that this would go some way to rectifying a bee population decimated by pesticides, whilst also producing honey as a ‘free-range’ alternative to the atrocities of honey bee farming.

But because honey bees make up just a small fraction of pollinators, lots of other bee species aren’t cultivated – like the famous Bumble Bee. Beyond that, there are actually hundreds of insects that pollinate our fields besides bees. This means that honey bees are steadily being over cultivated for the production of honey while out-competing other species and lessening biodiversity.

Beezantium is a recent piece of architecture that brilliantly calls attention to this by creating an informative space that doubles as a nest for numerous types of bees. It’s based on the style of a Victorian pavilion, set on the edge of a lake in Somerset, but set apart because of its genuine contribution towards the preservation of multiple bee species.

Beekeeper Paula Carnell explains : “There are numerous smaller habitats in the apiary provided for wild bees and solitary bees and the hives that were relocated into the apiary were wild swarms that already existed locally but needed to be moved as in various cases trees they were in had fallen. We designed the cladding specifically to encourage the creation of habitats for other species!” (full quote and more information here).

Unseasoned oak leaves holes for bees to climb in and nest, copper piping allows bees to easily enter and leave the building, and glass observation sections allow people to view the bees safely. Inside is an exhibition that enables people to be educated on different bee species and behaviour and the kind of things that encourage their natural flourishing amongst human settlements.

This is a positive example where the architects at Invisible Studios have thought long and hard about a design that genuinely contributes towards nature. The end result is architecture that is truly in tune with nature, bucking the trend of superficial eco-bling, and educating people along the way.

Beezantium interior, photograph by Jim Stephenson.

3. Trees

What better way to reflect an appreciation for nature than including trees, planters and hanging baskets on a new development? This trend is growing and is becoming more common with new developments, and whilst they bring obvious advantages to us human inhabitants, whether or not are these additions are really beneficial to the natural environment depends on several factors.

Trees are actually one of the most efficient ways to attract insects and increase pollination, especially when fully grown. It’s reckoned that a single, mature Lime tree offers enough food for a whole bee colony – as opposed to an entire field of wildflowers. Immediately you can see why trees like these are a more efficient source of natural beauty that genuinely contribute to the natural environment.

The difficulty is that trees on most new developments are saplings which don’t offer the same amount of food. Equally, many of the plants set in planters are highly cultivated and include insecticides that kill off wildlife anyway. It’s true that designing buildings with these installations may reduce our carbon footprint, but that’s as far as they go.

Another problem is the fact that growing plants and trees in planters disconnects them from mycorrhizal fungi which normally partner with plants. These enable them to easily absorb nutrients by extending their root area and exchanging nutrients with other plants. Growing naturally, trees are all inter-connected – it’s how they signal to each other to blossom in spring, and shed their leaves in autumn, so sitting them in isolated planters is akin to sending them into solitary confinement.

A more serious attempt to include plant life in architectural design would be to plan a way to include older trees on the site. This is already being trialled in relation to the HS2 railway project, where attempts are being made to relocate ancient trees and retain their natural benefits (which far outweigh that of saplings).

Two prominent examples show the difference between superficially including nature in building design, and doing it meaningfully. Thomas Heatherwick’s ‘1000 trees’ design exemplifies how buildings can include superficial greenery which offers little real benefit.

These trees sit in concrete eyries jutting out from the building in a small amount of soil, without any real benefit beyond the aesthetics.

On the other hand, Emilio Ambasz’ famous ACROS centre represents a serious attempt to preserve an entire green area while meeting human needs for space. His design retained the space for a public park and set of garden terraces that wound upwards from the ground to the roof of the building. In the process, over 50,000 plant types were incorporated, as well as water features and public access to the rooftop. It is as close as you can get to a pound-for-pound restoration of greenery that was subtracted by a building.

It seems like a lot of designs have a superficial connection to nature, or a resemblance to it, but often architects are only just beginning to dig down deeply enough to address the symbiotic relationship between humans and their shared environment with plants and animals. Currently too many designs aren’t deliberately eco-conscious and are human centred, with a specific intention to meet human needs (e.g. housing shortages). Budgetary restraints may well be the cause of architects tipping their hats to nature to gain public support, but with a little more thought and consideration, I would like to hope that designs could be tweaked to reflect a genuine understanding of what benefits the natural environment and well as us humans.